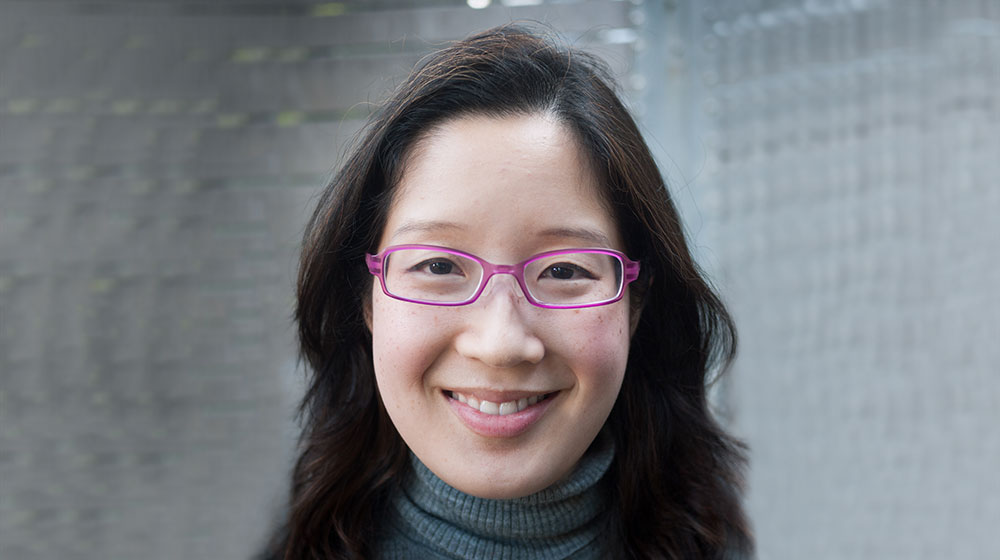

“It’s empowering to tell my patients, ‘I'm trying to figure out what causes migraine.’ I think it helps them to know that someone is taking them seriously and really working on this problem.” Maggie Waung, MD

Once a week, neurologist Dr. Maggie Waung spends the day at UCSF Medical Center visiting with patients suffering from debilitating migraines. These interactions drive her work in the lab, where she spends the bulk of her time investigating the brain stem circuits activated during headaches in the hopes of understanding if – and how – they contribute to the development of chronic migraines and subsequent medication overuse.

Why this work matters: “There are 37 million Americans suffering from migraines. If we can understand how these migraines are triggered, we may be able to develop more effective strategies to prevent or treat them.”

A shift in how we understand migraines: “For a long time, migraines were thought to result from a problem with the vasculature. That’s because the most effective migraine medications made the blood vessels constrict. Now we understand that migraines are related to how the brain processes external stimulation. People are light-sensitive, sound-sensitive, smell-sensitive. All of these external stimuli are bombarding the brain.”

What she’ll do with her Weill Scholar Award: “My project examines specific brain stem circuits that are involved in pain and reward behavior to see whether those circuits are active or changed in the presence of headache. I’m using a new tool known as optogenetics, which allows me to turn distinct neurons on and off with light.”

The benefits of this new technology: “Before the advent of optogenetics, people applied electrical stimulation to one area of the brain or used drugs to activate or inhibit neurons. The problem with that strategy is that any given area of the brain contains a collection of neurons traveling to different places. You can’t pick out which neurons you want to study with any precision. With optogenetics, you can fine-tune the stimulations so that you’re only activating or inhibiting neurons that go to a specific area.”

Why her migraine work stands out: “It’s a huge leap, because no one is really studying the brain stem or higher order structures in migraine in a circuit-specific manner. Researchers are looking at a much more generalized picture of the brain.”

The problem with medication: “Migraines become most worrisome when they affect people so profoundly that they can’t go about their daily lives – they can’t go to work, they can’t care for their families, they can’t spend time with friends. People with really severe migraines often take more and more medication to cope, and they wind up overusing them. We don’t know whether they’re taking more medication because their headaches are getting worse or whether their headaches are getting worse because they’re taking more medication. I want to look at this intersection between reward and pain to see if we can understand why this happens. It might also be a learned behavior – for example, when the pain medication stops working, the brain’s pathways may actually be changed, affecting a migraine patient’s ability to feel pain relief and encouraging them to take more.”

Why she loves working as a physician-scientist: “I used to wonder why some medications and strategies worked for patients and others didn’t. I didn’t have an answer for patients who desperately wanted to know why they were having these headaches. It’s empowering to tell my patients now, ‘Oh, I’m trying to figure out what causes migraine.’ I think it helps them to know that someone is taking them seriously and really working on this problem.”